- HD 1080

- Runtime: 20m.

- Status: Released

1

- Languages: en

- Country: United States of America

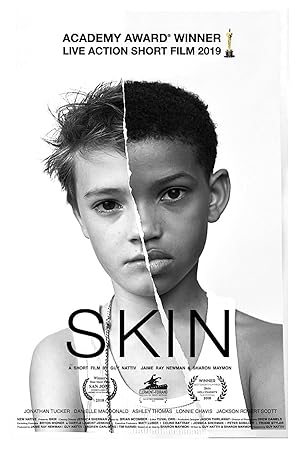

- Director: Guy Nattiv

- Stars: Danielle Macdonald, Jackson Robert Scott, Jonathan Tucker, Ashley Thomas, Lonnie Chavis

- keywords: supermarket, gun, aggression, based on true story, revenge, american culture, racism, hillbilly, racist comment, racial slur, hate crime, tattooing, grocery store, joyride, white supremacists, father son relationship, african american, short film, racial hatred, shooting, academy award, tattoos, racist attack

- Production_studio: New Native, Studio Mao

In a small supermarket in a blue collar town, a black man smiles at a 10 year old white boy across the checkout aisle. This innocuous moment sends two gangs into a ruthless war that ends with a shocking backlash.