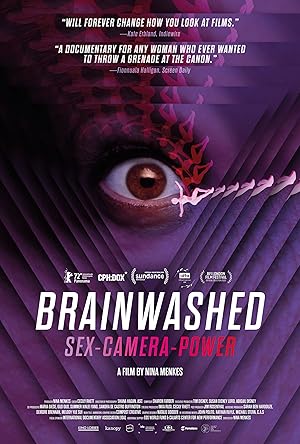

Brainwashed: Sex-Camera-Power (2022)

- HD 1080

- Runtime: 107m.

- Status: Released

1

- Languages: en

- Country: United States of America

- Director: Nina Menkes

- Stars: Nina Menkes, Rosanna Arquette, Penelope Spheeris, Catherine Hardwicke, Julie Dash

- keywords: sexism

- Production_studio: Menkesfilm

- providers: Kino Film Collection

Investigates the politics of cinematic shot design, and how this meta-level of filmmaking intersects with the twin epidemics of sexual abuse/assault and employment discrimination against women, with over 80 movie clips from 1896 - 2020.